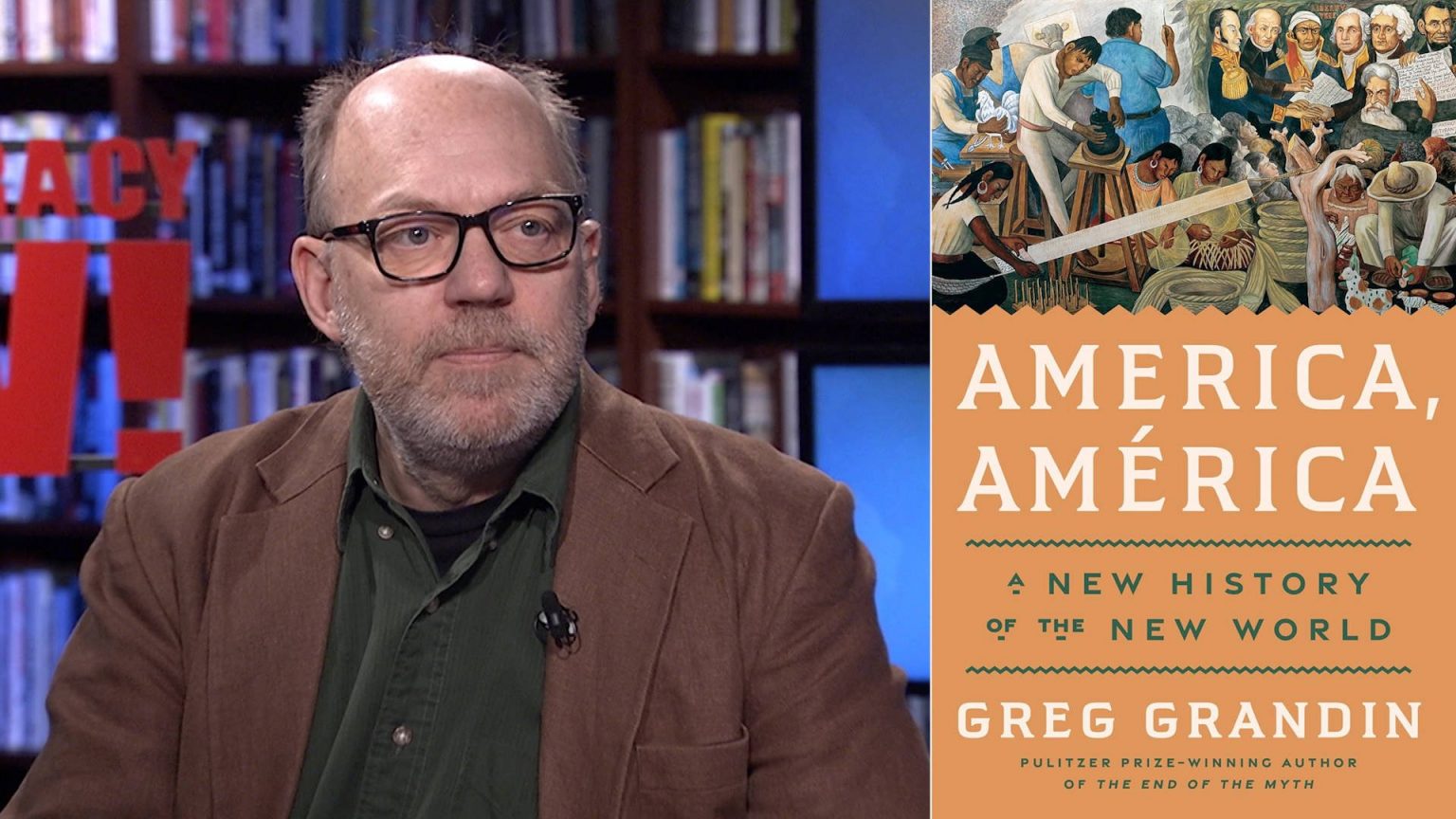

We spend the hour with acclaimed historian Greg Grandin discussing his new e-book, America, América: A New Historical past of the New World, which spans 5 centuries of North and South American historical past for the reason that Spanish conquest, together with the struggle towards fascism within the Thirties. He examines the U.S.-Latin American relationship beneath Trump, with a give attention to El Salvador, Panama, Ecuador and Cuba. Grandin additionally has a brand new piece for The Intercept that pulls on the e-book, headlined “The Lengthy Historical past of Lawlessness in U.S. Coverage Towards Latin America.” “If the USA actually has given up its position as superintending a world liberal order and the world is reverting again to those type of spheres of energy competitions, then Latin America turns into, primarily, far more vital,” says Grandin. We additionally proceed to look at the legacy of the late Pope Francis, the son of Italian immigrants to Argentina and the primary pope from Latin America. Grandin shares how the Catholic Church’s involvement within the conquest and colonization of the continent impacted the pope’s beliefs.

TRANSCRIPT

It is a rush transcript. Copy will not be in its closing type.

AMY GOODMAN: We start as we speak’s present with Greg Grandin, historical past professor at Yale College, Pulitzer Prize-winning writer, whose main new e-book is out this week, America, América: A New Historical past of the New World. He describes it as a, quote, “historical past of the trendy world, an inquiry into how centuries of American bloodshed and diplomacy didn’t simply form the political identities of the USA and Latin America but additionally gave rise to international governance — the liberal worldwide order that as we speak, many imagine, is in terminal disaster,” unquote.

The e-book spans 5 centuries, from the Spanish conquest to the primary Latin American pope, Francis, who was the archbishop of Buenos Aires, Argentina, and simply occurred to die on the age of 88 the day earlier than the e-book was launched. The Nation has revealed an excerpt from America, América in a piece headlined “Pope Francis Upheld the Spirit of Liberation Theology.” Greg Grandin additionally has new piece for The Intercept that pulls on the e-book, headlined “The Lengthy Historical past of Lawlessness in U.S. Coverage Towards Latin America.” He gained the Pulitzer Prize for his e-book The Finish of the Fable: From the Frontier to the Border Wall within the Thoughts of America.

Professor Grandin, welcome again to Democracy Now! Congratulations on the discharge of your e-book. I wish to start with that unbelievable second within the White Home, within the Oval Workplace. There’s President Trump sitting subsequent to the Salvadoran president, who calls himself a dictator, Nayib Bukele.

GREG GRANDIN: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: And the second of the USA and El Salvador, what this represented within the fruits of U.S.-Salvadoran relations, even going again — and I’m positive you’re going to return additional — to the ’80s, when the U.S. supported the paramilitaries and the navy in killing so many tens of 1000’s of Salvadorans, and now the connection is round this infamous mega-prison, the place President Trump says he now not has management over individuals he sends there.

GREG GRANDIN: Yeah. Properly, what struck — a lot of issues struck me about that encounter within the White Home. One was, as you talked about, Latin America is legendary for the type of type of political violence referred to as political disappearance, during which individuals had been actually simply kidnapped off the road and disappeared by safety forces. And again then, a component of that type of crime was the federal government would deny any information of it. And clearly, that wasn’t true. The federal government and the safety forces had been deeply concerned in finishing up and executing the disappearances. However that deniability created one other component of terror, the uncertainty the place their family members have gone, among the many relations, among the many survivors and the individuals who had been taken. You realize, authorities officers — individuals would waste their time going by way of labyrinth bureaucracies, asking questions, and the federal government officers would say, “Who is aware of? Possibly they went to Cuba. We don’t know.”

And what struck me was Bukele is like — there was no deniability this time, proper? Trump and — Bukele was like, “We acquired them. We all know the place they’re. And yeah, and we’re not going to offer them again.” That type of “f— you” impunity is a special type of terror, a special scale — proper? — that if the uncertainty of that first wave of disappearances created a type of horror and struggling amongst individuals, this sort of efficiency of omnipotence: “We have now them, and you may’t do something about it.” I additionally was struck by the glee during which they talked about it, simply the joking about it, like as in the event that they had been simply speaking about, you already know, not even human beings. The dehumanization, that was one other factor.

Let me simply additionally say, it is a little bit — it is a little little bit of a tangent, however Bukele does wish to joke round with slightly little bit of irony — though it’s not ironic in any respect, as a result of it’s true — that he’s a dictator. And, you already know, when FDR visited — Franklin Delano Roosevelt visited Vargas, the president in Brazil, who was a dictator however was additionally constructing a type of social state. He was a backer of social rights and increasing type of social welfare to the working class. When Vargas and FDR met, there was slightly protest towards Vargas. Vargas whispers to Roosevelt, “They name me a dictator.” And Roosevelt whispered again, “Me, too.” And so, they had been joking about being dictators, however in a very totally different circumstance, within the sense that they’re constructing social rights, they’re constructing a social state, they’re increasing financial, you already know, welfare states, the social rights to individuals, the place right here we have now two people who find themselves speaking about themselves as dictators and appearing as dictators as they dismantle what’s left of the New Deal.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And, Greg, after all, you’re acquainted, you’ve written previously about this historical past of lawlessness from the USA with regard to Latin America. And it appears to me that simply the identical cavalier perspective that was evinced on this dialogue within the White Home has been just about half and parcel of U.S. coverage. We’re going through now, as an example, Trump speaking about taking again Panama. And, in truth, there are literally extra U.S. troops now in Panama — quietly, the Panamanian authorities has allowed a few of the outdated navy bases to open up once more — on account of the strain from the Trump administration.

GREG GRANDIN: Yeah, and so they’ll quickly be in Ecuador additionally. Ecuador is vying to be a second El Salvador within the sense of a type of safety outpost. That is all within the context of — in a means, of dropping Colombia. I don’t know in the event that they’ve misplaced Colombia completely, however a left-wing Gustavo Petro was elected president, and he was an outdated rebel, and Colombia type of now not serving as a type of forecastle of U.S. energy within the area, and the USA now constituting El Salvador and Ecuador as these type of locations during which they’re projecting navy energy.

I imply, the larger query right here is, if the USA actually has given up its position as superintending a world liberal order and the world is reverting again to those type of spheres of energy competitions, then Latin America turns into, primarily, far more vital to the USA as a supply of sources, as a safety perimeter, during which with the ability to use sure international locations as navy bases turns into that rather more vital, because the world type of fragments up into — fragments into these spheres of affect, Russia and China and whatnot. And so, we’ll see much more of that, I feel, in Latin America within the coming years.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And I’m questioning — I wished to ask you particularly concerning the position of Guantánamo, as a result of most Individuals don’t actually grasp the truth that the USA is holding a navy base in Cuba actually towards the desires of the Cuban authorities nonetheless in any case of those years. What permits this to proceed to happen?

GREG GRANDIN: Properly, what permits it to proceed to happen is simply absolute uncooked energy, the facility of the USA. The US, when it took Cuba and it took Puerto Rico and the Philippines and Guam in 1898 on this conflict, Spanish — conflict towards Spain, it carved out Guantánamo as a navy base, as a coaling station, you already know. And it had an finish date, and I feel that finish date handed, for the least. However as soon as the Cuban Revolution occurred in 1959, the U.S. ignored it and simply stored Guantánamo as its personal type of enclave throughout the revolutionary island.

And, after all, you already know, Latin America has lengthy been a spot during which the USA, as a rising empire, has used as a receptacle to solid off its undesirable or the those that it thought-about type of outdoors the pale of belonging to the nation. Previous to the Civil Warfare, many individuals thought that the USA might avert a conflict over slavery by principally sending all its free individuals of coloration to Latin America, to Central America, to Mexico, to Panama, to Haiti, as a means of lessening racial tensions. That, after all, didn’t occur. Within the Nineties, Guantánamo turned the place the place the U.S. held refugee Haitians, following that nation’s coup towards Aristide, in inhuman situations. After which, after all, in the course of the “conflict on terror,” Guantánamo turned synonymous with a conflict that authorized classes might now not — might now not type of set up, proper? So there was no time period for these prisoners who didn’t belong to any — or we weren’t preventing their nations; we had been preventing them. So it got here up with enemy combatants, and Guantánamo turned the place during which they had been housed. So, there’s a protracted historical past of this, after all. And sure, it’s on the island of Cuba, and the irony of that, since Cuba is likely one of the few international locations which have lengthy resisted U.S. militarism.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And I wished to, to begin with, congratulate you in your new e-book, America, América, and likewise ask you why you felt that it was obligatory to jot down this new historical past of the Western Hemisphere, particularly presently.

GREG GRANDIN: Properly, I believed — there’s loads of books that have a look at the affect of Latin America and the USA, you already know, and El Norte, and the way the Americas are actually all one. However what I used to be actually making an attempt to do is go slightly bit additional and take into consideration how the stress between, first, the British and Spanish colonial system, and, then, between Spanish Republicans and the USA, provides rise to a set of political ideas that turn out to be the inspiration of the worldwide order. You realize, when individuals consider the founding of the United Nations or the founding of the League of Nations or what — you already know, what they speak about, the rules-based order, they typically look to Europe. They give the impression of being to Europe’s relationship with its former colonies. And that’s the histories that get written. However, you already know, in some ways, the concepts that turn out to be foundational to the world after the tip of World Warfare II had been created in Latin America.

When you consider it, Juan, Latin America — the USA turns into a nation, a single nation, on what they imagined to be an empty continent. Clearly, it wasn’t an empty continent. Clearly, the Spanish Empire diddled there. There was Indigenous sovereignties throughout the Plains and throughout the Rockies. And the USA revives the doctrine of conquest to be able to justify shifting west as quick as it might probably.

Latin America comes into the world, six republics already a League of Nations. They arrive into the world already a United Nations. They need to study — there was nothing like that in historical past. Europe wasn’t like that. Europe was a group of empires, you already know, and monarchies, that had been then increasing their colonial attain, sending their gunboats into the Indian Ocean and flitting round China. Latin America was a real assemblage of bounded nations, and so they needed to discover ways to get alongside. They each threatened one another and so they legitimated one another, and legitimated one another as a result of if one republic can throw off Spanish Catholicism and declare itself unbiased, then one other one might. However they threatened one another, as a result of beneath the outdated guidelines of legislation, what was to cease Argentina from doing what the USA was doing and say, “We would like the Pacific. Let’s simply ship our settlers over throughout the mountains and begin taking land from the Chileans or the Mapuche or no matter”? However, after all, they weren’t going to do this. That they had to determine a brand new idea of sovereignty, a brand new mind-set about how nations dwell collectively.

And one of many first issues they got here up with is the premise that nations aren’t essentially inherently aggressive. They critiqued each the USA’s doctrine of conquest, and so they critiqued the Previous World’s steadiness of energy, the presumption that the best way you’ll obtain stability and stasis is by every nation or empire urgent their pursuits, and that creates a type of countervailing pressure. They thought that was inherently unstable and would all the time result in conflict. What they got here up with was a imaginative and prescient of internationalism during which the primary precept was that nations shared a type of widespread goal, a shared set of pursuits, and that they’ll work collectively cooperatively by way of diplomacy.

In addition they got here up with the concept the boundaries of the outdated colonial system had been the boundaries that they had been going to just accept. They will not be excellent. They might have been imposed by the colonial system. However that’s what we have now. There’s no frontiers. We’re not going to be pushing. And now, in some ways, this was a type of a really perfect sort of imaginative and prescient. There was loads of wars in Latin America, notably within the nineteenth century, and skirmishes. You realize, Brazil wished rubber, and that was in Peru. And there was numerous, you already know, water skirmishes. However all of these skirmishes had been negotiated beneath the premise that the boundaries had been actual, that the wars of conquest and wars of aggression had been unlawful. And all of those concepts are what ultimately makes it into the United Nations Constitution.

AMY GOODMAN: Greg Grandin, I wished to ask you, comply with up on you mentioning Argentina and likewise comply with up on the pope. And it goes to a significant theme in your e-book. Democracy Now! broadcast from Buenos Aires for a number of days. We adopted the Moms of the Disappeared within the Plaza de Mayo within the — the ladies who misplaced their youngsters and grandchildren, demanding to know the place they had been. And also you comply with the place of the Catholic Church all through Latin America, a particularly conservative pressure, but additionally the liberation theology, that was so vital, and so they had been counter to one another, whether or not we’re speaking concerning the church allying with the U.S.-backed regimes in Guatemala, in El Salvador. In El Salvador, after all, Archbishop Romero was gunned down March twenty fourth, 1980. Argentina, that’s the place Pope Francis was from, the primary Latin American pope. He was there in the course of the Soiled Warfare, from ’76 to ’83. And I do know there’s controversy round — it’s fairly murky what occurred then. And what his position was and his relation to liberation theology on the time, might you go into this?

GREG GRANDIN: Properly, yeah. I imply, Pope Francis, in some ways, was a quintessential Latin American. He was born throughout an period during which social actions, labor unions and peasant leagues had been coming into the general public sphere, demanding social rights. In his case, he grew up beneath Peronism. I don’t know whether or not — I don’t know his place on Perón. I don’t know whether or not his household was Peronist. I do not know. However he definitely was immersed in that type of — you already know, the bursting into the general public sphere of the plebeian. And he was a priest by way of the Soiled Warfare, as you mentioned, and thru all of the turmoil of the Nineteen Seventies. And there’s a murky interval, and there’s accusations and counter-accusations. And it appears as if a lot of the forces of the left have — you already know, the query was whether or not he did sufficient to guard different Jesuits as the top of the Jesuit order in Argentina, towards the dictatorship.

AMY GOODMAN: Notably the story of two clergymen?

GREG GRANDIN: And notably, yeah, two Jesuit clergymen. And one, to his dying day, believed that Saint Francis — Saint Francis — that Pope Francis gave him up and —

AMY GOODMAN: Named for Saint Francis of Assisi.

GREG GRANDIN: Yeah, named for Saint Francis. And the opposite priest forgave and mentioned, “No, I imagine he did all he might to guard us as a lot as he might.”

He wasn’t a liberation theologian. Actually, many thought he was conservative. And there was some speak when he was voted pope that he was picked as a result of he would function a counterforce to the political left, which at the moment, for those who keep in mind, was Chávez and Kirchner in Argentina, and, you already know, it was a really robust motion in Latin America in the course of the — within the first decade of the 2000s.

However, you already know, historical past has this manner of, you already know, doing the surprising. And he turned out to be fairly a humanist, progressive pope, notably when positioned throughout the bigger perspective of the non secular schism between conservative Christianity, which was on the rise, during which there’s alliances between conservative Catholics and dominionist evangelicals that wish to principally take over the political sphere — and appear to be doing a reasonably good job of it on this nation and elsewhere — and that wing of the Catholic Church that also imagines itself as emancipationist, as liberationist, as egalitarian. And he clearly sided with that wing, with the liberationist wing, in his pronouncements, in his very being, his simply — one in every of his final acts was calling for a ceasefire in Gaza, which The New York Instances didn’t hassle to say in its obituary, which is fascinating, and which itself —

AMY GOODMAN: Sunday, on Easter Day.

GREG GRANDIN: Yeah, which was wonderful. So, you already know, I imply, it was the identical factor with Óscar Romero. When Óscar Romero was picked to be bishop of El Salvador, he was picked as a result of they thought he was conservative. They thought he would defend the established order. You realize, the landed class was very pleased with Óscar Romero. And the expertise of residing in historical past has the tendency to radicalize individuals generally. And generally it radicalizes them in the correct route, within the extra humanist route. And that occurred with Óscar Romero, and it occurred, I feel, with Francis.

AMY GOODMAN: And he dies, proper earlier than, giving that speech, which is broadcast all through El Salvador, Archbishop Romero, straight addressing the Salvadoran navy — sadly, the U.S.-backed Salvadoran navy — saying, “I urge you, I” —

GREG GRANDIN: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: — “beseech you, I demand you set down your arms.”

GREG GRANDIN: Yeah, I imply, it’s fairly a heresy — proper? — to order your navy to not obey their officers.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Greg, I wished to ask you — this debate between the humanist and elitist and conservative wings of the Catholic Church, as you observe in your e-book, has a protracted historical past. And also you’ve spent fairly a little bit of time speaking concerning the Sixteenth-century debates between two Dominican clergymen, Bartolomé de las Casas and Francisco de Vitoria. What was the substance of that debate, and what’s its significance traditionally, particularly by way of the impression that the Native presence on America had on European thought?

GREG GRANDIN: Yeah, nicely, the e-book does begin with the conquest, and it begins with the conquest in all of its horror and all of its struggling. I imply, we’re speaking — some demographers name it the best human mortality occasion in historical past. They estimate that there have been most likely about 90 million individuals residing within the Americas, and inside a century, 90% of them had been gone. And, you already know, Spanish Catholicism, when the Spanish Empire arrived and claimed dominion, claimed sovereignty, they knew they had been presiding over a populated land. And it sparked a debate among the many theologians about tips on how to justify dominion. You realize, the reconquest of Iberia, the driving Muslims and Islam off of Iberia, was justifiable as a result of —

AMY GOODMAN: Spain.

GREG GRANDIN: What’s that?

AMY GOODMAN: Spain.

GREG GRANDIN: Spain. Spain, sure. Iberia, Spain — was justified as a result of they claimed that Spain was Christian earlier than Muslim or Islam arrived, and subsequently, what they had been doing was simply taking again land that had been taken from them. However they couldn’t make that argument within the conquest — proper? — as a result of Native Individuals hadn’t recognized Christ, and subsequently, they couldn’t deny Christ. And so, they needed to give you a brand new justification for why Spain had the correct to presume sovereignty over the Americas.

And there was a small group of critics, together with de las Casas, together with Francisco de Vitoria — most of them had been Dominicans, additionally Franciscans — that started to argue that you just couldn’t discover any foundation of legitimacy. You definitely had no legitimacy to enslave them. And there emerged — within the face of the horror of the conquest and all its unimaginable struggling, there emerged a critique, a fairly cohesive critique, towards conquest, towards slavery, nearly — a critique that just about went to the purpose of pacifism, and a critique that insisted that every one humanity was one. Bartolomé de las Casas is legendary for a line, “All humanity is one.” The precise right English translation was one thing related, “The entire human lineage is one,” that means lineage from Adam and Eve. However he insisted on the equality of individuals. There was no distinction between Native Individuals and Europeans, in his thoughts. And that is the inspiration, I argue, of contemporary political thought, and notably his rejection of the doctrine of conquest.

And now, why that’s vital — and I type of hint that out by way of the e-book, and this — certainly not does it ameliorate any of the brutality of the conquistadores and what they did and the enslavement of Native Individuals and that biggest human mortality occasion in human historical past that I discussed earlier. Nevertheless it did create and consolidate a pole throughout the Catholic Church that continued, an emancipationist, abolitionist pole that continued. And why it’s vital, it’s vital for a few causes. One is, it was vital for the character of the Spanish American — Spanish Empire throughout the Americas, which I can come again to, however in a while, when Spanish American Republicans start to interrupt from Spain and arrange their very own unbiased nations, after which have to start out contending with the USA, which is reviving the doctrine of conquest to justify its enlargement west, these Latin American intellectuals and political leaders had already at their disposal a reasonably coherent critique of conquest, a reasonably coherent critique of slavery, that they then — that what have been utilized to Spain, they then utilized to the USA. And it’s that rigidity, and it’s that type of persistence of this ethic, that turns into the inspiration of the worldwide order.

Now, I’ll additionally say, the opposite factor that’s particular concerning the Spanish Empire is that the Spanish Empire made no — the Spanish Empire knew it was an empire over individuals. Native Individuals had been the primary factor. They had been the individuals who extracted the wealth out of the Americas and created the world’s first common foreign money. However they had been additionally the middle of Spanish moralism. You realize, what the Native Individuals had been, as they had been outlined by theology, is what justified the Spanish Empire.

Now, while you bounce forward a few centuries and also you get to British colonialism, there’s no dialogue about Native Individuals. There’s no dialogue about, you already know, the justification of tips on how to justify colonialism. Actually, the London Firm in 1607, once they had been sitting round, they’d a gathering, and so they mentioned, “Properly, perhaps we must always — perhaps we must always concern a doc that justifies Jamestown and justifies what we wish to do in New England.” And, you already know, they’ve this debate, and so they’re totally conscious that for a century the Spanish have been debating this for a yr — for a century. And so they principally come to the conclusion, “You realize, the Spanish clergymen, the Dominicans and the theologians have been debating this for a century, and so they nonetheless can’t give you a workable justification for Spanish conquest, so perhaps it’s higher we don’t say something in any respect. We simply preserve our mouths quiet and simply do it.” So, that evasion of accountability is a significant strut within the e-book.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re going to interrupt after which come again to this dialogue. I wish to speak concerning the position of Latin America in preventing fascism, from the ’30s till now. And in addition, I wish to ask you concerning the radical journalist Ernest Gruening. Greg Grandin is our visitor, historical past professor at Yale College, Pulitzer Prize-winning writer, whose new e-book is America, América: A New Historical past of the New World. Stick with us.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: “Las Tumbas” by Puerto Rico’s Ismael Rivera. That is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org. I’m Amy Goodman, with Juan González.

We’re spending the hour with historical past professor from Yale College, Pulitzer Prize-winning writer, whose e-book is out this week, America, América: A New Historical past of the New World — professor Greg Grandin is our visitor.

So, let’s speak. We speak about Orbán in Hungary. We speak about Holocaust. We speak about those that fought fascism. Nevertheless it isn’t as a lot talked about, those that fought fascism in Latin America, and its key position, and what the USA, and particularly those that are preventing the authoritarian tendency, can study from our southern neighbor.

GREG GRANDIN: Properly, Latin America had the nice fortune of attending to struggle fascism simply because the New Deal was consolidating in the USA, and a shift in the best way — away from intervention and a shift away from Washington defending U.S. capitalists and U.S. funding in any respect prices. So, FDR had a way more eclectic method to Latin America, and principally he gave the left room to maneuver in Latin America.

I imply, Spain, in some ways, loads of grand strategists had been afraid that, principally, the Spanish — the type of battle that you just noticed in Spain between Franco, representing a Spanish nationalism, Catholic nationalism, allied with Mussolini, allied with Hitler, and preventing type of extra liberal currents inside — liberal and radical currents inside Spain, was principally only a preview of a battle that will ultimately drift throughout the Atlantic and take over all of Latin America, as a result of the sociology was very related — servile peasants, giant landed landowners, you already know, militarism, a type of conservative Catholic hierarchy. Many individuals noticed within the Mexican Revolution a type of mirror of the Spanish Civil Warfare. And plenty of theorists felt Latin America might go both means. And this isn’t even — this isn’t even speaking concerning the affect of Germany and Japan and Italy inside Latin America. So, Latin America was actually on the knife’s edge within the Thirties.

And the New Deal, principally — and it’s notably the left-wing members of the New Deal who had been very a lot enthusiastic about Latin America, labored very laborious to offer house to social democrats and create a type of actually bulked liberalism to a strong conception of social rights and materials enchancment in individuals’s lives as a means of countering fascism. Like, they didn’t beat fascists by simply calling them fascists; they beat fascism by providing an alternate. And that different was some type of socialism or some type of social democracy or some type of social liberalism. And in a single nation after one other, this sort of, you already know, variations on social democracy come to energy and ally with the USA. And by the point the conflict begins, Latin America is just about — with the type of exception of Argentina, is just about allied with the USA behind Washington.

So, when FDR went to conflict in 1941, he rallied not simply his nation, he rallied the entire hemisphere. The US actually — and Latin America was indispensable to the USA. The US didn’t need to struggle one battle for sources, as a result of it had Latin America. After which, Brazil, with that bulge that goes into the Atlantic, was a significant transport route, that Roosevelt referred to as it the “Atlantic trampoline,” as a result of the planes would land in Natal after which go straight off — then go bounce over to North Africa. And an incredible quantity of conflict materials made it to Europe by way of that route. So, Latin America, in some ways, each materially and ideologically, was key to preventing fascism, each as a part of the conflict, however then internally preventing the fascists inside their very own international locations.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Properly, Greg, there have been, as you talked about — you talked about Argentina. Clearly, Juan Perón’s period was one which was a minimum of sympathetic to the Nazis. And in addition, the Trujillo dictatorship was — had loads of sympathies for — definitely for Franco and for fascism. Trujillo at one level had the assassination of a Spanish Republican, Galíndez, the notorious Galíndez case. He was assassinated at Trujillo’s orders in the USA. So there was a present, a fascist present, that ultimately led to many Nazis settling in locations like Argentina and Brazil after the conflict.

GREG GRANDIN: Yeah, completely. And that’s what I discussed, that in some ways, individuals — the concern was that every one of Latin America would turn out to be Spain, that there could be a Spanish Civil Warfare all through the entire of Latin America between the forces of progress and the forces of fascism. And that didn’t occur. And, you already know, in most locations — in lots of locations, it’s as a result of democrats and social democrats got here to energy. Somewhere else, just like the Dominican Republic, with Trujillo, it’s as a result of they noticed which means the winds had been blowing, and so they acquired on board with the Allies.

After which, after the conflict, as you mentioned, it does turn out to be a type of — in some methods, a continuation of World Warfare II. Many socialists thought that the struggle towards fascism didn’t finish with the dropping of the atomic bomb or European victory over Germany, that now that fascists had been defeated in Europe, the fascists at dwelling needed to be defeated — the Trujillos, the Somozas, the Batistas. You realize, within the Caribbean, they created the Caribbean Legion, which they noticed in — you already know, they didn’t see it as like wanting forward in direction of the Chilly Warfare. They noticed it as a continuation of World Warfare II, that we’re going to construct a Caribbean Legion, and we’re going to take out Trujillo, we’re going to take out Somoza, we’re going to take out Batista and all of the little Hitlers which are nonetheless type of, you already know, populating Latin America. And, after all, that didn’t occur.

What occurred was that the Chilly Warfare shifted the phrases of debate, and the USA shifted its help away from social democrats and the concept democracy and growth went hand in hand, in direction of an concept that order and stability and growth went hand in hand, and commenced shifting all of its surveillance actions away from fascists and in direction of communists and in direction of the left. And, after all, the irony is that in World Warfare II, the USA invested all of those international locations with huge capability, navy capability. There was a lend-lease program in Latin America, the place Chile acquired navy gear, and Brazil acquired navy gear. And after the conflict, these weapons had been turned on the left.

There’s no higher instance of this than in Chile in 1948. Chile, a Common Entrance authorities was elected in 1947, however then there was a militant strike in 1948, a miner strike in 1948. And the federal government turned from the type of ethos of the Common Entrance to placing down the miners’ strike and principally mobilizing airplanes and navy warships to destroy and occupy giant parts of northern Chile. And concerned in that was a younger navy officer named Augusto Pinochet, who started rounding up strikers and placing them in a jail camp in northern Chile. So that you see how all this navy weaponry that was — so, the road between preventing and facilitating fascism in Latin America was all the time very fungible.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And, Greg, we have now solely a minute or two left, however I wished to ask you concerning the Latinization of the USA. There’s over 62 million individuals of Latin American descent residing in the USA as we speak. How a lot is that this presence part of the historical past that you just write about?

GREG GRANDIN: Properly, I don’t go in — nicely, the e-book was lengthy sufficient, so I couldn’t go too far into the migration query. However definitely, and so they convey with them the identical type of polarization, identical type of conflicts. I imply, you already know, they revitalized union actions in Nevada, in Los Angeles. You realize, when Latin Individuals, they arrive to the USA, they don’t suppose that democracy means simply particular person rights. They imagine in issues like healthcare. They imagine in issues like public schooling.

However then, then again, there’s additionally a bunch of immigrants that come fleeing international locations that they contemplate have gone too far to the left. And so they’ve created their headquarters in Florida, proper? Like, you already know, what we thought was the waning affect of older generations of right-wing Cubans has been reinvigorated by waves of Hondurans and Venezuelans that think about themselves fleeing left-wing tyrants, Nicaraguans, and so it’s contributed to the turning of Florida into this laboratory of Trumpism and headquarters of a — and Mar-a-Lago as a type of headquarters of a pan-American Trumpism, pan-hemisphere Trumpism.

AMY GOODMAN: What shocked you most in researching this, oh, 700-page epic work?

GREG GRANDIN: Oh, nicely, I suppose what shocked me most — nicely, didn’t — nicely, what I used to be so stunned with was how the Good Neighbor — we all know “the Good Neighbor coverage” as a phrase, related to Franklin Roosevelt as his therapy of Latin America. Nevertheless it was additionally the phrase that they used to get out the vote in his 1936 reelection. And it turned a sort — the Good Neighbor Leagues had been arrange as a counter to the Liberty Leagues, explicitly anti-fascist. They had been meant to embody a sure type of cultural pluralism and acceptance of the range of the nation. And so they had been understood explicitly as a substitute for the white supremacist Liberty Leagues. And so they principally delivered the vote to Roosevelt. He gained 20 million votes. He gained extra votes —

AMY GOODMAN: Ten seconds.

GREG GRANDIN: — than every other human being in historical past up till that time. And he did so operating on a coverage of social democracy.

AMY GOODMAN: Greg Grandin, our visitor for the hour, historical past professor at Yale College, Pulitzer Prize-winning writer. His new e-book, America, América: A New Historical past of the New World. I’m Amy Goodman, with Juan González, for one more version of Democracy Now!

Indignant, shocked, overwhelmed? Take motion: Assist unbiased media.

We’ve borne witness to a chaotic first few months in Trump’s presidency.

During the last months, every government order has delivered shock and bewilderment — a core a part of a technique to make the right-wing flip really feel inevitable and overwhelming. However, as organizer Sandra Avalos implored us to recollect in Truthout final November, “Collectively, we’re extra highly effective than Trump.”

Certainly, the Trump administration is pushing by way of government orders, however — as we’ve reported at Truthout — many are in authorized limbo and face courtroom challenges from unions and civil rights teams. Efforts to quash anti-racist instructing and DEI packages are stalled by schooling college, workers, and college students refusing to conform. And communities throughout the nation are coming collectively to boost the alarm on ICE raids, inform neighbors of their civil rights, and shield one another in shifting reveals of solidarity.

It will likely be a protracted struggle forward. And as nonprofit motion media, Truthout plans to be there documenting and uplifting resistance.

As we undertake this life-sustaining work, we attraction to your help. We have now 24 hours left in our fundraiser: Please, for those who discover worth in what we do, be part of our neighborhood of sustainers by making a month-to-month or one-time present.

Source link