An eerie silence pervades the historic center of Culiacan, capital of the Mexican state of Sinaloa, where infighting among one of the world’s biggest drug cartels has left hundreds of people dead since September.

As night falls on Paseo del Angel, the city’s entertainment quarter, a popular restaurant offering Japanese-Mexican fusion cuisine that was booked out nightly just a few months ago is virtually empty.

A nail salon and a pastry shop on the same street have “for sale” signs in the window.

“Life in Culiacan has almost disappeared,” Miguel Taniyama, owner of the Clan Taniyama restaurant, lamented.

Luis Antonio Rojas for The Washington Post via Getty Images

Years of relative quiet in Sinaloa, a predominantly agricultural state home to the notorious cartel of the same name, were shattered in September when two rival factions of the drug gang went to war.

Since then, each week has brought a grim litany of shootouts, abductions, bodies dumped in the street and vehicles and businesses set alight, sending Culiacan’s 800,000 residents scrambling for cover.

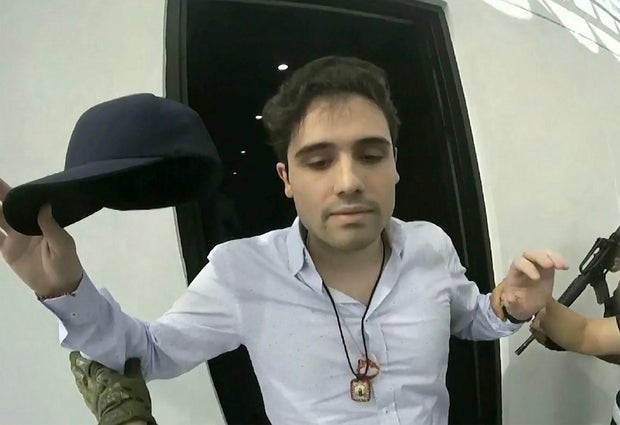

The bloodletting began on September 9 after details emerged of how the son of the cartel’s jailed founder Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman reportedly double-crossed the cartel’s other co-founder, Ismael “El Mayo” Zambada.

Zambada was arrested on U.S. soil on July 25 after allegedly being kidnapped in Mexico and delivered to U.S. authorities against his will.

Zambada claimed he was ambushed by Joaquin Guzman Lopez, one of “El Chapol”‘s sons, who he said lured him onto a plane that was headed for the United States, where “El Chapo” himself is serving a life sentence.

The ensuing war between the cartel’s “Mayos” and “Chapitos” has left more than 400 people dead and hundreds missing, according to the state prosecutor’s office. According to an indictment by the U.S. Justice Department, the Chapitos and their cartel associates have used corkscrews, electrocution and hot chiles to torture their rivals while some of their victims were “fed dead or alive to tigers.”

The local Noroeste newspaper said 519 people had been killed in an explosion of violence that shows no signs of abating. Bodies have appeared across the city, often left slung out on the streets or in cars with either sombreros on their heads or pizza slices or boxes pegged onto them with knives. The pizzas and sombreros have become informal symbols for the warring cartel factions, underscoring the brutality of their warfare.

Eduardo Verdugo / AP

At least 10 people were killed on Monday, the state prosecutor’s office said.

Last week, five bodies were found outside the Autonomous University of Sinaloa, which promptly suspended classes and switched to remote learning.

Cartel’s stranglehold on Culiacan

The Sinaloa Cartel, one of Mexico’s biggest drug trafficking organizations, was built on cocaine smuggling but over the past decade has changed focus to feeding the U.S. opioid addiction.

The U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration in June said the gang was “largely responsible for the massive influx of fentanyl” into the country over the past eight years.

CEPROPIE via AP File

The cartel’s stranglehold on Culiacan was evident in 2019, when Mexico’s security forces attempted to arrest another of El Chapo’s sons, Ovidio Guzman Lopez.

The operation ended in humiliation for the government, which was forced to free the drug lord after the cartel launched a massive assault on the city.

While Culiacan recovered quickly from that episode — and Ovidio was later recaptured — the succession war now raging within the cartel has brought the local economy to the brink of collapse.

At least 30,000 people have lost their jobs, representing about a third of all social welfare recipients, according to the city’s chamber of commerce.

The violence has affected all aspects of daily life.

With many people fearing going out into the street, some companies have reinstated pandemic-era remote working.

The second-division Dorados de Sinaloa football club, which had late Argentine legend Diego Maradona for a coach in 2018-2019, has temporarily relocated from Culiacan to Tijuana, some 1,500 kilometers away.

“I want my son back”

Around 11,000 soldiers backed with armored vehicles and planes have been deployed to Culiacan to try to quell the violence.

In October, the army said it had killed 19 suspected cartel members and arrested one local leader in its bloodiest clashes with narco-traffickers in years.

More than 450,000 people have been murdered in Mexico since the state launched a war on drugs in 2006.

Over 100,000 people are missing.

To try lure people back onto the streets, Taniyama, the chef, organized a giant festival on November 21, with live music and lashings of Sinaloa’s signature dish, aguachile, a shrimp ceviche.

“We’ve been locked up for 70 days and scared out of our wits…Today we’re starting to live again!” he told the gathering.

But there was no respite from the suffering for the families of those caught up in the violence.

Rosa Lidia Felix, 56, has not heard from her 28-year-old son Jose Tomas since he went missing on November 1.

“Please, I want my son back,” she wept.

Source link