Your help helps us to inform the story

From reproductive rights to local weather change to Massive Tech, The Impartial is on the bottom when the story is growing. Whether or not it is investigating the financials of Elon Musk’s pro-Trump PAC or producing our newest documentary, ‘The A Phrase’, which shines a lightweight on the American girls combating for reproductive rights, we all know how essential it’s to parse out the info from the messaging.

At such a crucial second in US historical past, we’d like reporters on the bottom. Your donation permits us to maintain sending journalists to talk to either side of the story.

The Impartial is trusted by People throughout the complete political spectrum. And in contrast to many different high quality information shops, we select to not lock People out of our reporting and evaluation with paywalls. We imagine high quality journalism ought to be out there to everybody, paid for by those that can afford it.

Your help makes all of the distinction.

Sitting in a dimly-lit bamboo shelter on this planet’s largest refugee camp, Rohingya Muslims like Azizur Rehman could possibly be forgiven for hating Aung San Suu Kyi.

5 years in the past, the then-leader of Myanmar appeared on the Worldwide Courtroom of Justice to disclaim the Rohingya have been victims of genocide by her nation’s navy, a lot to the shock of the remainder of the world.

But Rehman, 34, speaks enthusiastically from Cox’s Bazar in Bangladesh in regards to the now jailed Myanmar leader and her father Basic Aung San, Myanmar’s independence hero, who in 1946 declared that Myanmar’s residents “will reside collectively and die collectively” and guaranteed full rights and privileges for the Rohingya. One yr later, he was assassinated.

“I don’t suppose she (Suu Kyi) is the true enemy of the Rohingya,” he tells The Impartial. “She was only a rag doll who by no means had absolute energy.”

As a substitute he blames the military itself and the Mogh Baghi – a typical time period utilized by refugees for the Arakan Military, essentially the most highly effective Buddhist insurgent group in Myanmar accused of forcefully displacing tens of 1000’s of Rohingya.

“I don’t know if I, or the tens of 1000’s of individuals like me, will ever return to Burma. However I imagine Aung San Suu Kyi’s launch from detention might awaken her conscience and provides her an opportunity to redeem herself for not talking up for the Rohingya when she was in energy.”

Rehman, who fled Rakhine State throughout the 2017 mass exodus, now works as a group chief within the camp, serving to those that proceed to flee battle and destruction since General Min Aung Hlaing led a navy coup that overthrew Suu Kyi’s democratically elected authorities in February 2021.

As Myanmar plunges deeper into civil war under military rule, Rohingya refugees like Rehman are reassessing their views on the jailed chief.

Determined and annoyed with the ever-waning consideration on one of many world’s most persecuted communities, many Rohingya in exile cling to the assumption that the discharge of Suu Kyi will present them some hope for repatriation to Myanmar.

Rehman’s perspective seems to be consultant of most of the Rohingya who’ve fled throughout the border to Cox’s Bazar.

Now in her fourth year of solitary confinement in Myanmar, Suu Kyi, 79, was long celebrated as a global democratic icon for standing up to the Myanmar generals, but later fell from grace due to her silence and perceived complicity in the brutal military crackdown of 2017 – an operation that led to mass killings and displacement of over 700,000 Rohingya.

As the Myanmar military faced accusations of “widespread and systematic clearance operations,” including mass murder, rape, and destruction of Rohingya villages, Suu Kyi stood at The Hague in 2019 and dismissed the claims. She argued that the allegations against the military presented an “incomplete and misleading factual picture” and blamed the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA) for triggering what she described as an “internal conflict”.

While Suu Kyi conceded that disproportionate military force may have been used and civilians killed, she said the acts did not constitute genocide. At Bangladesh’s refugee camp, some refugees at the time shouted “liar, liar, shame!” as they watched Suu Kyi on television.

Five years later, in November last year, the International Criminal Court’s prosecutor Karim Ahmad Khan requested an arrest warrant in opposition to Basic Hlaing “for the crimes in opposition to humanity of deportation and persecution of the Rohingya, dedicated in Myanmar, and partly in Bangladesh”. This request is presently underneath assessment by ICC judges, who will decide whether or not to problem the warrant.

Umma Hanee, 75, remembers watching the ICJ hearing where Suu Kyi defended the army against accusations of genocide.

“It was due to the power of the general that she was unable to speak up for the Rohingyas at that time and General Min Aung Hlaing was actually the person in power, who used to direct violence against people in Rakhine state,” Hanee says.

“Rohingyas are the citizens of Myanmar and everyone, including Suu Kyi should raise their voice for us.”

Mohammad Shakir, 35, blames General Hlaing for pushing the Mogh Baghi into the Rakhine state, calling him the “main culprit” of the crisis in Myanmar.

“General Min Aung Hlaing has controlled the power in Myanmar,” he asserts.

Shakir believes that if “Rohingyas now stand with her (Suu Kyi) and demand her release, she might testify that Rohingya did not commit violence, but the junta did”.

The refugees in Bangladesh say they follow the happenings in Myanmar and updates on Suu Kyi through TV and online news on their phones despite bad reception in parts of the camps – once a forested area inhabited by wild animals, now home to nearly a million displaced people.

It is not the first time Suu Kyu has been under house arrest. Arrested three times before, she has spent more than 18 years of her life with little company and no connection with the outside world.

Once likened to Mahatma Gandhi and Nelson Mandela, she was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for her non-violent struggle for democracy and human rights in Myanmar in 1991. At the time, she was under house arrest imposed by the military junta for her role in leading the pro-democracy movement.

Her younger son Kim Aris, who lives in London, has raised concerns over his mother’s health in interviews with The Impartial and made a direct enchantment to the military-run authorities in Naypyidaw to launch her on the fourth anniversary of the 2021 coup.

The Impartial TV’s documentary Cancelled: The Rise and Fall of Aung San Suu Kyi shines a lightweight on her continued imprisonment.

In Cox’s Bazaar, Sabikun Nahar, who has lived in a cramped 12ft by 12ft shelter for two years, tells how she once owned a large piece of land in Myanmar.

She alleges that the land is now occupied by the military and used for conducting activities against their people.

Nahar believes that Suu Kyi’s downfall is intrinsically linked to the 2017 crisis.

“If the 2017 influx had not happened, she might not have been jailed. Even when she was in power, she was making efforts to repatriate us. But this angered Min Aung Hlaing, and he jailed her. That’s why we are still unable to return to Myanmar,” she says.

Many Rohingya had high hopes when Suu Kyi became Myanmar’s first civilian leader after decades of military rule—largely because of her father’s legacy. General Aung San had openly referred to the Rohingya as “our own people”, a recognition later erased by successive military regimes.

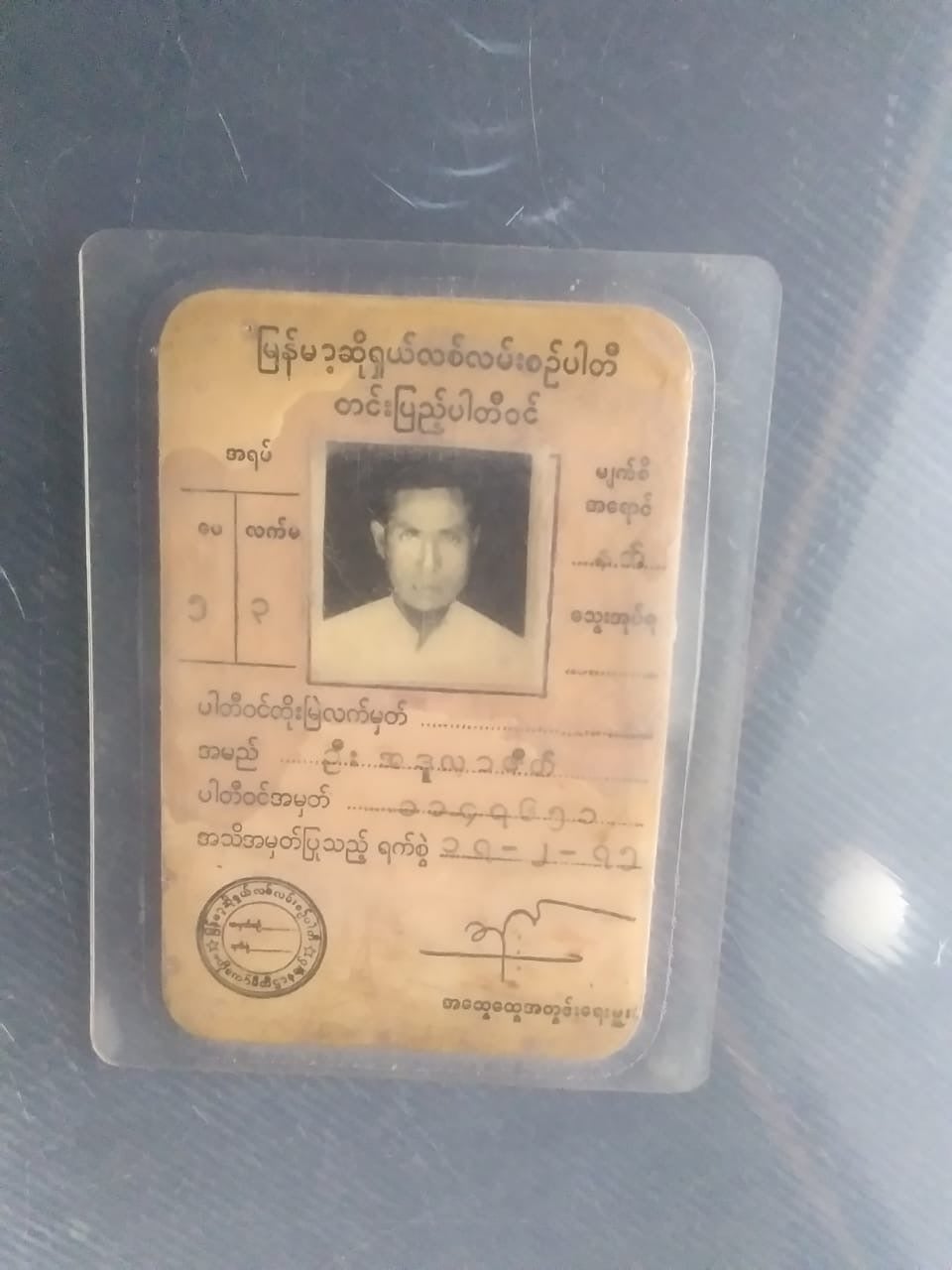

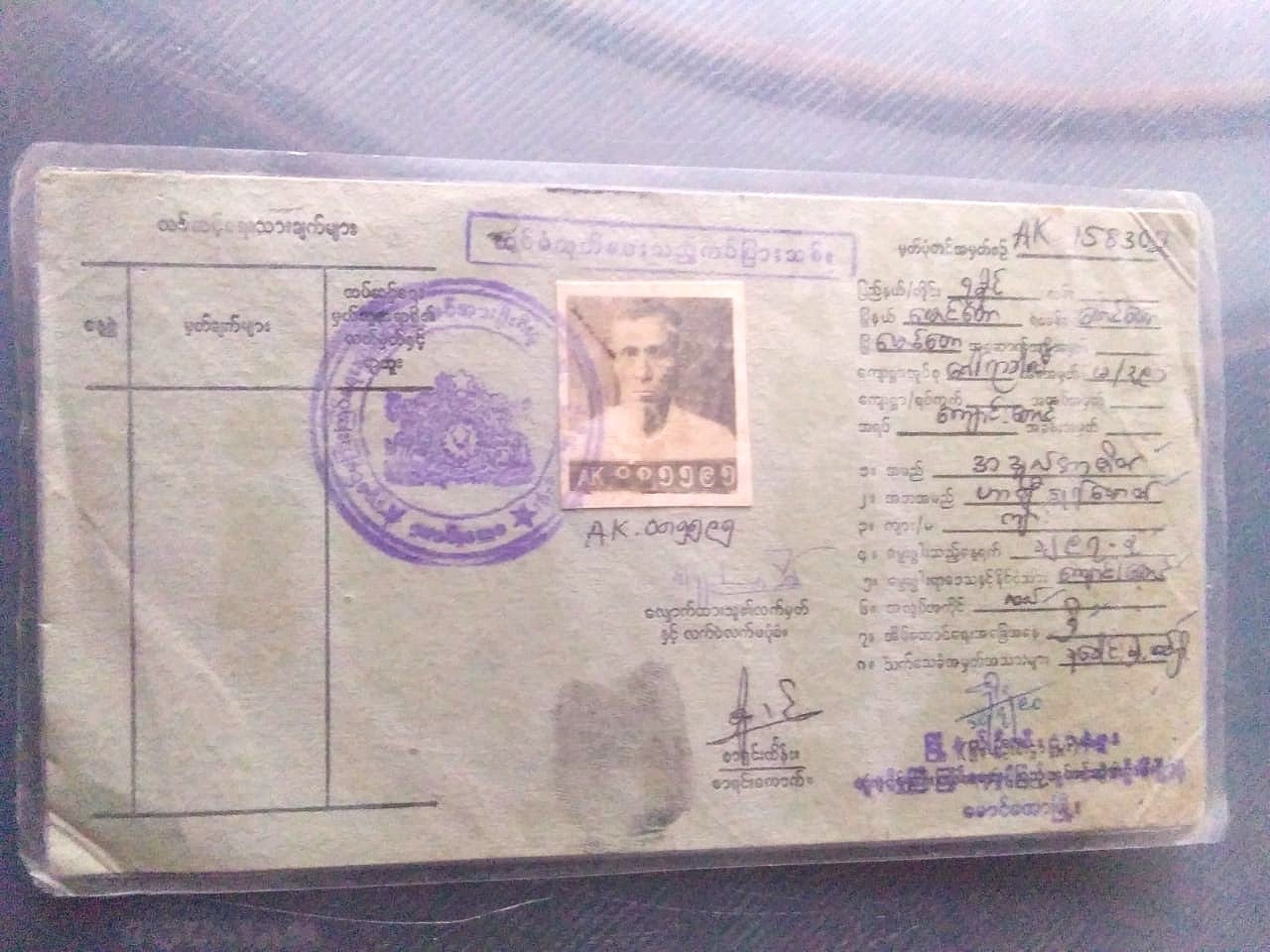

Rehman and others remember the “red identity cards” issued under Aung San’s leadership—proof of their Burmese citizenship—only to be replaced later with white cards, marking them as Bengalis and Muslims rather than Myanmar nationals.

“That was the only identity proof my family held for a short period of time. Since then, we are fighting for our identity and our homeland, facing systematic oppression at the hands of the junta,” Rehman says.

Abdul Karim, a 60-year-old refugee whose mother had a similar identity card, lamented that Suu Kyi did not fulfil her commitment to ensure peace in Rakhine state and remembered her father “who was more sympathetic to them.

“We voted for her in the election as she was our only hope. But she failed us and the world,” he says.

The influx of Rohingyas into the already overcrowded camps in neighbouring Bangladesh has never stopped since 2017. It has been exacerbated by the 2021 coup which has unleashed a civil war in parts of the country, especially in the Rakhine state. It is one of the poorest among the country’s seven states and has a vast majority of the population of Rohingya Muslims.

Human rights groups have raised concerns over the living conditions in the camps where the majority of the population solely relied on the UN’s funding for food and healthcare.

The United Nations’ food agency earlier this week said it was planning to slash food rations for Rohingya refugees by greater than half from subsequent month, a transfer that activists say would trigger widespread malnutrition among the many already susceptible group.

The Independent spoke to those who have escaped violence, rapes and forced conscription of their nation. The combating in Myanmar has intensified between insurgent teams and the navy because the latter claimed energy and overthrew the democratically elected authorities.

Within the final yr, the navy has misplaced big swaths of territory to the insurgent teams, together with in almost all of Rakhine State, in response to experiences. It has additionally misplaced territory within the west and northern Shan State within the east of Myanmar and enormous components of Kachin State within the north.

Hanee, a septuagenarian, says there are textbooks in Myanmar on Basic Aung San whereas Suu Kyi had her contribution written and erased with the a number of navy coups the nation has seen.

She says the one solution to deliver peace in Myanmar is after Suu Kyi is launched and the Arakan Military is held accountable and brought over.

Noor Hashim, a refugee himself who works with trafficking victims on the camps, says Suu Kyi is considered one of them.

“Suu Kyi has been the sufferer of the navy like us,” he explains, demanding that she ought to be launched and allowed to spend the remainder of the times together with her household.

Source link